First Place: Anastasia Taylor - Lind

Artist Statement: The National Womb: Baby boom in Nagorno Karabakh

The National Womb: Baby boom in Nagorno Karabakh

In 2008 Nagorno Karabakh's de facto government introduced the "birth encouragement program" which distributes cash payments to newlyweds for each baby born, with the aim of repopulating the region after the devastating 1991-1994 war.

The conflict started when the Soviet Union collapsed. Nagorno Karabakh's ethnic Armenians went to war with Azerbaijan, backed by neighboring Armenia. The war left 65,000 ethnic Armenians and a further 40,000 ethnic Azeris displaced. The Muslim Azeri population never returned, and neither did many of the Armenians who had fled. While a ceasefire was declared in 1994, there has been no peace settlement yet between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

On the 2nd of September this year, Nagorno Karabakh celebrated 20 years of independence, yet remains unrecognized by the international community. Life is not easy in the republic. There is high unemployment, low salaries, few opportunities and the young continue to leave in search of better futures abroad.

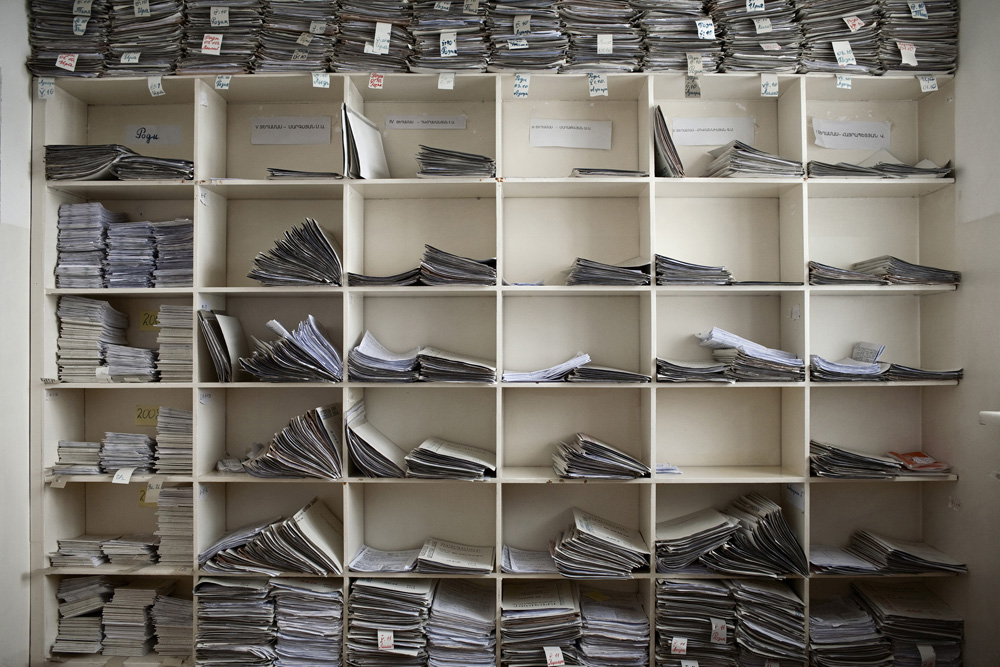

Since its introduction 4 years ago, the "birth encouragement program" is credited for an increased birthrate of 25.5% from 2145 recorded births in 2007 to 2694 in 2010. The program is administered by the Department of Social Security which oversees the payments to married couples of approximately €575 (300,000 ad) at their wedding. They are paid €190 (100,000 ad) for the first baby born, €380 (200,000 ad) for the second, €950 (500,000 ad) for the third and €1350 (700,000 ad) for a fourth. Families with 6 children under the age of 18 are given a house.

Nagorno Karabakhs baby boom was also sparked in 2008 by a mass wedding on the 16th October that was held for 674 couples. The event was funded by private donations from several wealthy Armenian diaspora businessmen including Levon Hairapetian and Ruben Vardanian and couples who participated receive privately funded higher payments of €1400 ($2000) for the mass wedding, €1400 ($2000) for the first child, €3500 ($5000) for the second and increasing amounts up to €70,000 ($100,000) for the seventh. Figures on the 1st July 2011 show that a total of 693 babies had been born to these mass wedding couples so far. These payments are quite substantial in a region where the average monthly salary is €35 ($50).

Family life in Nagorno Kharabak is deeply traditional and conservative. When women marry they are expected to live with the husbands family and stay at home to raise children and care for their mother and father-in-law. Even within the home men and women live parallel but separate lives. A mans role is to provide for the family financially and fathers play only a small part in child rearing. So, what of the young women who are being paid to increase their nations population, the communities of expectant and young mothers and their daily struggles as women in this unrecognized republic??

Stepanakert Maternity Hospital is the largest in Nagorno Karabakh, and with an average of 6 to 7 babies being born everyday it is the frontline of the republic's baby boom. It was here that I met 24 year old Marianna Avanesyan, and photographed her giving birth to her second daughter, Nare, on the 8th July 2011. Marianna and her husband Sevak Gurgenyan got married in the 2008 mass wedding and have so far received approximately €2800 ($4000) for their wedding and first child from the private businessmen who organised and funded the wedding. They expect a further €2100 ($3000) shortly for the birth of their second child. At home in Askeran Marianna told me that the possibility of war with Azerbaijan is always on her mind. As a child their family home was destroyed, and Marianna recalls seeing aeroplanes dropping bombs as she watched from their living room window, before retreating to the apartment's communal cellar where the family hid for months at a time. It is these memories, Marianna says, that make her spoil her 2 daughters so much: "If war comes and I am poor and can no longer buy things for them, at least they would have had a normal childhood for this short time"

19 year old Narine Hakobyan shared the same ward as Marianna and after she was discharged I went to stay with her in the remote mountainous village of Kolatak. Despite her young age, Narine already has 2 children. Her husband is in the Armenian Army, serving very close to the border with Azerbaijan and only comes home to visit them every few weeks. Narine's days consist of domestic chores: cooking, cleaning, washing and feeding the children, which she shares with her mother-in-law Azniv and her young sister-in-law Lilit. She used the birth encouragement program payments to buy bedroom furniture and open a savings account at a bank. She told me that it was important to spend the money on something that will remain, something for the children to keep. Narine got married at 16, to escape an unhappy home life with her father and unloving stepmother. As a young women in this society, the only way out was to marry and move to her husbands house. Narine calls her in-laws mum and dad and says they are like parents to her. The family lives a simple rural existence, raising cows and sheep in the pastures above their home. Narine describes the social welfare system in Nagorno Karabakh as "very good" and the birth encouragement payments as a "big support". Humbly she mentions that they must be an even bigger support for families poorer than her own.

Then there was Rosa Sargsyan who has 8 children, between the ages of 8 months and 17 years old. They live in Nor Aresh, a suburb of Stepanakert, where the Department of Social Security has housed 8 large families as part of their welfare program that gives free homes to families with more than 6 children under the age of 18. The demands of bringing up 8 children had clearly taken its toll on Rosa, and although only in her mid-thirties it would have been easy to imagine that she was a much older woman. She says she didn't really plan to have such a big family and it was her husband Samvel, 11 years her senior and a war veteran, who wanted so many children. Rosa and Samvel are largely self sufficient, feeding 10 mouths predominantly on produce from their large vegetable garden and home reared chickens and rabbits. Rosa's day evolves entirely around her family and it is a never ending battle to keep the brood clean, fed and in line. Then there is the cleaning, washing and housework, which often gets over looked in light of more pressing issues like cooking, watering the garden and tending to the animals. Rosa is a loving and caring mother, who has dedicated her whole life to raising children. Her oldest daughter Angelina (17) says she'd like to get a job and work when she finishes school, and then get married and have 2 children, no more.

The "birth encouragement program" is clearly working and the figures are undisputable. Payments are being made efficiently and the support is accessible to everyone. All of those I spoke to seemed happy and grateful for the money that is offered from both private donors and the government. The repopulation of Nagorno Karabakh is something everyone I met felt passionately about and the women were proud to be doing their part for this hopeful state. However, I found no evidence that the allure of thousands of euros was enough to convince couples to have a higher number of children then they had already decide to, and the mothers I photographed went uninfluenced by the "birth encouragement program" when it came to family planning. What the program does do is demonstrate the government's commitment to increasing the republic's population and represent the national psyche that values large families and traditional parenting roles.

Perhaps there are questions, that are yet to be answered, about the long term affects of encouraging so many young women to become mothers. In a region as economically deprived as Nagorno Karabakh, is the solution simply to increase the birth rate, without first improving education, infrastructure, employment opportunities and raising the standard of living for these future generations? Otherwise, the baby boom children may grow up to leave in search of better lives abroad, just like the youth of today.